7:45 am

I wake up in a one-room, lake-facing cabin at the only guest residence in at least 1,000 square miles. The sun, indifferent, peaks through my window. I hear the chatter of rare birds already in routine, and my eyes follow the bare wood of the walls and floor to the white overhanging mosquito netting that has fallen over my feet in the night. My bearings, or at least what remains of them, come rushing back.

8:00 am – 8:20 am

Breakfast is taken looking out on muddy Lake Murray from the wooden, wraparound veranda of Lake Murray Lodge. The morning’s nutrition includes fresh jungle fruit from the furious, swampy lake-jungle all around us. After breakfast, approximately forty minutes are lost without explanation, as sometimes happens in Papua New Guinea.

9 am or so

With a small cast of wild cards and castaways beside us, our crew of four walks the looping path down to the lake’s edge, where lodge boatman “Monster”—a quiet, solidly built local who may have once gone by Kevin—is waiting at the wheel of a 24-foot motorboat. Its thin, metallic hull is trying its hardest to shimmer through stains of mud. An outboard motor hangs off the back, surely outdated, but in this world of hand-dug canoes it is everything new, all at once. Monster is either a legend or a traitor for commanding it.

We displace our weight around Monster, and with a roar we rush out onto Lake Murray. The sun is beating, and we cruise past a few paddling canoers, swampland and something approximating the final frontier. We zigzag methodically through Lake Murray’s splintering arms, as though someone knows the way around in these parts of clans and subclans. Sunscreen is passed around, and anticipation builds around what’s next: a visit to a village that has welcomed one—one—previous group of western tourists. I am lent a bucket hat, which will remain in my possession for more than a year.

I’ll say 10 am

Monster takes us around yet another peninsula of wild earth, and on the other side we point our bow at a muddy outcrop a thousand feet ahead. We glide toward it, decidedly slowing as the scene ahead introduces a thatched-roof structure—nestled between two identical lakeside trees—and then people, and then some style of commotion. And then, wait—it is dozens of people, or is it hundreds, covering every inch of the mud, dancing, clothed and half-clothed in every color in a wholehearted appeal to all they are greeting as new. We get closer, and the silence is broken by singing, banging drums and the ringing sensation flooding my body to the ends of my limbs.

Idling just offshore, Monster’s boat spins slowly with the current as the welcome ceremony crescendos. The boat stops suddenly as we ram into the muddy shore, but the frenzy in front of us is still wild. Perhaps that was not the crescendo. We remain seated. It is unspoken, but we will wait until we recognize a coda to disembark.

The scene quiets, and wading ankle-deep, we transition between worlds. I proceed to shake close to 25 open hands, one after the other. There are smiles, mostly, but skepticism, too. A still-energized procession takes our group to an open-air men’s lodge up and over a hill, where the full picture of a life very different comes into view. We later learn the men’s lodge—basically a large rectangular space of dirt beneath a thatched roof—was completed just two weeks prior with this specific welcome in mind.

Between 10 am and the afternoon

In Uskov village, where for our hosts we represent the impartiality of changing times, we are met with no structure, no instruction, no guidance. There is a single precedent for this specific exchange in all of history. There is bewilderment and curiosity on both sides, and there are stretches of silence and unease in the middle.

In the men’s lodge, we kick things off with an electric press conference-like meeting in which much of the time is spent feeling out who should talk. We sit on a support at the front like show-and-tell exhibits, within legs’ reach of a pool of wide-eyed children. Adults and elders—maybe 400 of them—have stuffed themselves in all the way to the back. We introduce ourselves, elders are thanked, we are thanked as liaisons of future commerce and cultural exchange, and an elder in the back raises his voice while pointedly reminding us what’s at stake (his people’s well-being). We are in over our heads.

The tension dissipates and we aimlessly spill outside the lodge. What next? There is no orchestrated pottery-making demonstration; the visit is to be free-form, the exchange of perspective unbridled. And so naturally, we follow the children. Ally rounds up a circular game of some sort. Will asks to bang the drum. I am told to dance, and I do, like a fool. We follow our brains as they discharge what is received as a greatest hits collection from the western world. With touchstones like leap frog—with which Will and I incite euphoria among the dozens children running alongside us—we are closing the gap between our ways of life. And so we keep firing. It is like a high that we follow faithfully.

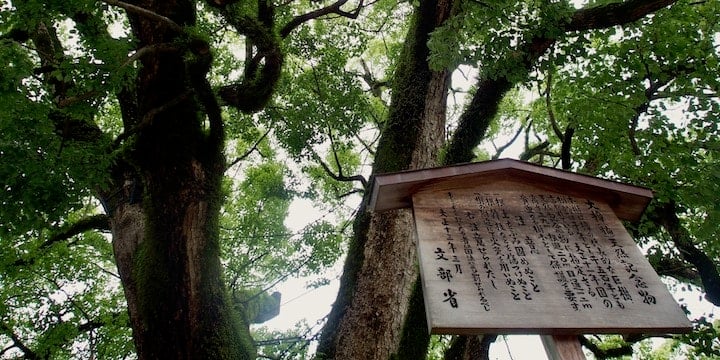

We ask to see the tiny schoolhouse, and the children oblige. Inside, up a step (we’re beside a lake), in front of desks holding half-coconuts full of mud for body-painting instruction, we challenge their geography and math. Will leaves a note on the blackboard. I wander my way into conversation with the village Work Director, who lays out some key and processable numbers: 829 people in the village based on his last census.

A rugby ball is at one time unavailable. Later it appears, and outside the schoolhouse it is spiraled through the air between westerners and villagers. Another procession begins and swallows Jenny and then goes on for far too long. Eventually, an end is requested as much to save Jenny as to keep us on any kind of schedule, for in Papua New Guinea, time is flexible.

Near the end of our visit, I wave at a small girl, and she screams and flees with such sincerity that all of us, western guests and Papuan hosts, laugh together.

Our departure takes us back down the hill. We pass through the sticky mud again and another round of ceremonious handshakes. Will goes for a swim, illuminating all who’ve walked with us back to the water on the aesthetics of the white body.

Maybe 2 pm?

On the trip back to the lodge, the boat stops at a swimming nook somehow trusted in the crocodile-infested waters of Lake Murray. Monster quiets the motor, and we all jump in for a cool-down. It is nice feeling so weightless.

Later than that

We arrive back at Lake Murray Lodge wet but drying, exhausted but invigorated. There is time for a sensational nap in my cabin, and a little reading.

Even later

In this section of Lake Murray, there is a “sunset market” every day at the presumed time. At that time yesterday, we brought the whole thing to a standstill as we perused the long grassy stretch of seated vendors, many encircled by kids. All eyes were on us. I bought a “spear,” a local cigarette of tobacco rolled in repurposed newspaper printed somewhere I’m not clear on and which would later be kinder to my head than expected.

Tonight, a contingent of our crew has made a return trip to the market to once again shatter perspective and also procure catfish fresh from the lake. Back at the lodge, the two women training as in-house cooks slather the grilled fish in soy sauce and chilis from the market and we soak up the night’s first few SP beers with some pre-dinner magic.

???

Later, when it is dark out, the best thing happens. We head out on Monster’s boat to search for crocodiles. The jug of Canada Club comes with us, its contents splashing about the glass bottle as we walk down to the boat under the moonlight. In this part of the world, at this hour, the dark is darker, but the moon still finds a way to be brighter and bigger than I have ever seen it.

Out on the water, the roar of the motor is the only sound breaking incomprehensible silence. With flashlight beams we pick out a few pairs of crocodile eyes by the side of the lake—maybe where we swam earlier, and maybe not. All around us is a world so different, but we are starting to understand what it means to have bearings here. Tomorrow, we will continue the process. For now, there is still more whiskey, and we head home.

In Part 3: 5 photos from Papua New Guinea. Part 1 is available here.

For more on travel to Papua New Guinea, check out papuanewguinea.travel and pngtours.com.

Sounds like it’s time for me to visit PNG :)

Yea, that’s the gist!

Great info, thanks for the share!