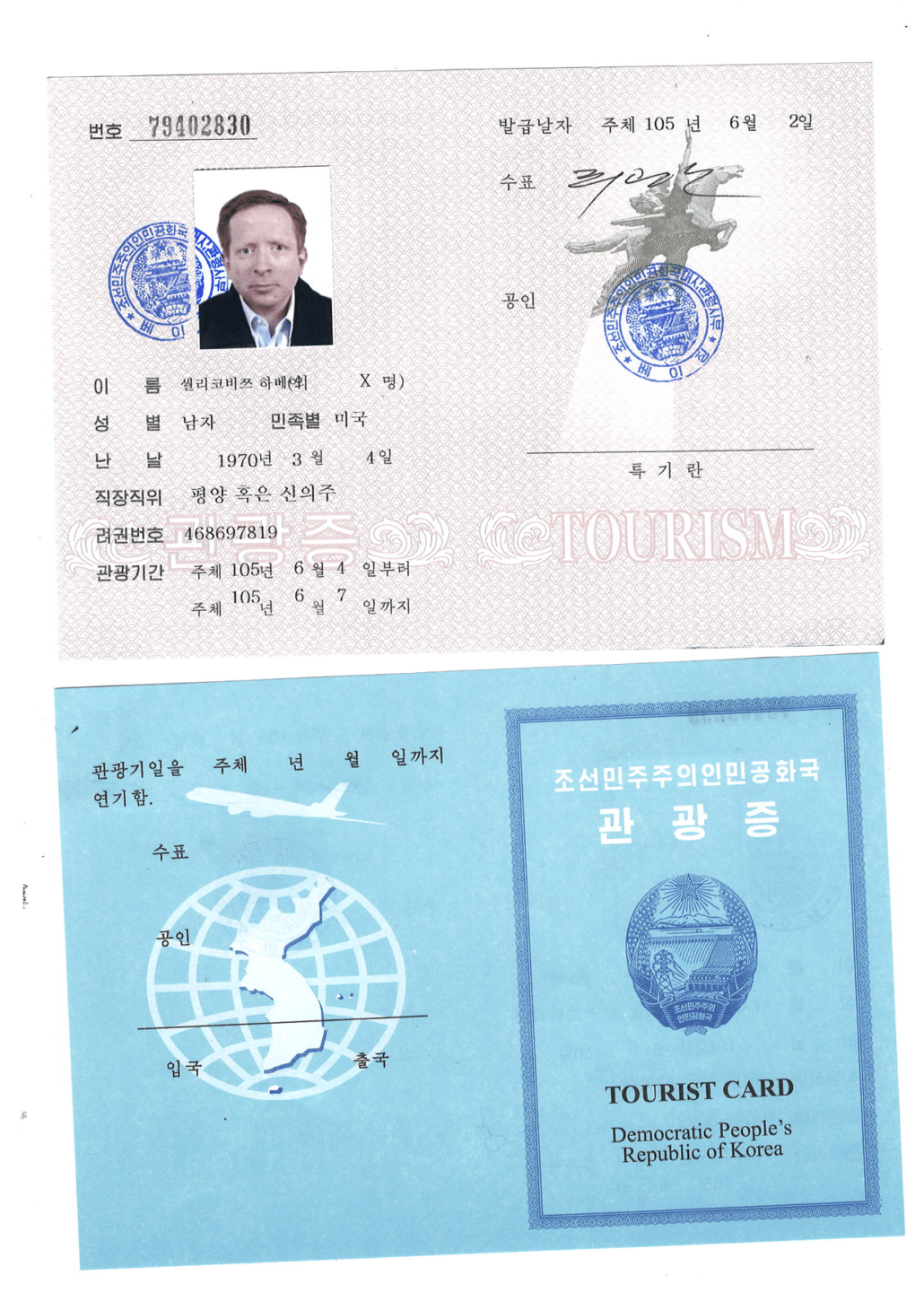

In June of 2016 I entered the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), popularly known as North Korea. Now there’s a sentence that, just a few years ago, I never would have thought I’d be in position to write. In this post I’ll address some questions you might have about traveling to North Korea, and about the experience that I had.

Are you crazy? What were you thinking, going to North Korea? You’re lucky that you were even allowed to leave North Korea when you were done. Americans get arrested all the time there, and often for no reason at all.

During the run-up to my visit to North Korea, many of my friends back in the US expressed variations of this sentiment. They harbored what in my view was an exaggerated concern that I was likely to be detained—i.e., arrested and not permitted to exit the country. Their fears were probably amplified due to the detainment of American university student Otto Warmbier in January 2016. Warmbier, who was about to fly to Beijing, China, at the end of his tour, was yanked off the plane and arrested on charges of stealing a government propaganda poster from the Yanggakdo International Hotel (the Pyongyang hotel in which most tourists lodge). He subsequently confessed and was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. Video evidence supposedly established Warmbier’s guilt.

While Warmbier’s sentence was draconian, I wasn’t terribly worried about being subjected to a similar fate. In fact, on average, one American tourist per year is detained in North Korea. This is out of roughly 2,000 Americans who descend upon that country annually. (Overall, some 5,000 Westerners visit North Korea every year.) So even if being arrested were a random occurrence (and I don’t believe it is), the odds of that fate befalling me were extremely low. I was confident that so long as I obeyed the laws, and didn’t do or say anything stupid, I would be permitted to return to Beijing on my own scheduled flight out of North Korea.

Further helping me feel comfortable, I had arranged my travel to the DPRK through Koryo Tours, a company run by Brits that’s been taking Westerners into the DPRK since the 1990s, and whose General Manager has personally visited the DPRK over 150 times. Thus, I felt that I was organizing my trip through a company that knows how things work in the DPRK and enjoys excellent relations with the North Korean government. (With that said, admittedly I wasn’t accompanied by any Koryo Tours personnel while inside the country, as I had opted for a private tour. If I’d gone on a group tour through the company, one of its representatives would have led the tour in conjunction with the two local guides.)

I made sure to follow my guides’ instructions to the letter. For example: I was directed to remain in the company of my local guides at all times when outside my hotel. I complied. When we visited the Mansudae Grand Monument, which features giant statues of deceased former DPRK leaders Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il (see the photo at the top of this blog post), I was admonished not to take any selfies in front of the monument in “mocking” poses—and specifically, not to imitate the poses of either of the statues. Not only did I obey that demand, but I even acceded to pressure from my guides to bow down before the statues, and to buy a bouquet of flowers from a nearby vendor and lay it at their bases. Would I have been arrested if I’d “disrespected” the dead dictators by declining to bow before their statues? I’ll never know, but I wasn’t about to take that risk.

I also went out of my way to constantly tell my guides what I thought they wanted to hear—or at least to restrain myself from articulating what I was really thinking. For example, at one point one of my two local guides asked me, “How does your experience here compare with what you heard about us in your country?” If I’d been honest, I would have replied along the lines of, “This is exactly the oppressive totalitarian society I expected!” Instead, I said something like, “I’m keeping an open mind. And I see people just going about and living their lives, just like anywhere else.” I noted that, for instance, I’d seen citizens playing volleyball and chess along the Taedong River. Of course, it would have been more accurate for me to say, “They don’t have any human rights, but they’re going about their lives because what else can they do?”

Another memorable exchange occurred during my excursion to the demilitarized zone (DMZ) that serves as a buffer between North Korea and South Korea. A North Korean soldier briefly rode in the van with my guides and me, and in fact sat next to me, as we were driving between sites in the DMZ. The soldier turned to me and asked, “So you understand that the United States started the Korean War?” Although I knew that it was North Korea that had started the war, I readily responded, “Yes.” But I added, “Hey, don’t blame me! I wasn’t alive when it happened.”

Why would you choose to travel to North Korea, knowing that your money would support a dictator who oppresses his people and has nuclear weapons?

I understand and respect this viewpoint. Initially I would note that the meager income that accrues to the regime from tourism is a drop in the bucket compared to the aid it receives from China. The money that I and other visitors spend in the country has no impact in keeping Kim Jong-un in power.

Even acknowledging the moral objection to making any monetary contribution to a horrible government, my trip needs to be viewed in the context of my philosophy of travel. My goal is to see as much of the world as possible, and inevitably that will involve visiting some places whose leaders do very bad things. (Another example of such a regime is Cuba, which has become a trendy destination despite being a dictatorship with comparable human rights abuses to North Korea. I would hope that anyone who condemns travel to North Korea feels the same way about the island nation that’s about 90 miles south of Key West, Florida.) But I think there’s value in seeing those places, and bearing witness with my own eyes to the circumstances in those countries. Moreover, I’m committed to telling the truth about my experiences in all places to which I travel. I hope that I do so in this post. Certainly, I have no intention of becoming the next Dennis Rodman. :)

Okay, so you decided to go to the DPRK. How does one enter that country? And isn’t it illegal for Americans to go there?

In answering this question, it’s important to mention that Westerners are only permitted to visit the DPRK through a government-approved tour company. You can’t just go onto the internet and book a flight into the DPRK, nor can you use a site like Expedia to reserve a hotel room in Pyongyang. All the transportation arrangements and hotel bookings will be handled by your tour company. In addition, your tour company will take care of obtaining your North Korean entry visa. About that visa: At least you don’t have to part with your passport during the application process as you do when seeking visas from many other countries. I merely had to email my tour company a scanned copy of my passport and a scanned passport-sized photo.

Only one commercial airline flies into North Korea from any other countries: Air Koryo, the national flag carrier of the DPRK. Air Koryo operates scheduled passenger service between Pyongyang’s Sunan International Airport and three Chinese cities (Beijing, Shanghai and Shenyang), as well as Vladivostok, Russia. If you fly Air Koryo, you’ll be able to say that you took the airline that has been rated by Skytrax, based on its survey of airline passengers, as the very worst commercial airline in the world for six years in a row. In each of those years, it’s been the world’s only airline that has earned one star out of five. To be honest, though, I found Air Koryo to be a perfectly fine, if unexceptional, airline. It may not have much of an in-flight entertainment system, but the service and comfort on the flight were adequate. Indeed, the cabin of the Russian-made Tupolev jet wasn’t much different from the interior of a Boeing 737 or Airbus A320.

The itinerary constructed by your tour company will almost certainly have you flying into Pyongyang from Beijing, as I did; and you will most likely fly from Pyongyang back to Beijing when your tour has wrapped up. As an alternative for some travelers, rail service connects North Korea with China; a couple of Australians whom I met during my trip made their return journey to Beijing via train. I was told that Americans aren’t permitted to take the train out of North Korea, and I’m not sure why that is. However, visitors from other countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom may have the option of taking the train in lieu of flying.

Ordinarily, it’s not possible to travel directly, by any mode of transportation, between North Korea and South Korea. Oh, and the US government doesn’t prohibit its citizens from traveling to North Korea, although the US State Department’s website “strongly urges” Americans not to go there.

Is it true that airport officials will scour the hard drives of all your electronic devices when you’re entering and leaving North Korea?

That didn’t happen to me. Nevertheless, for a Western tourist at least, making it through the immigration and customs checkpoint in Pyongyang’s airport is quite a production.

First I had to remove all my electronic devices from both my checked luggage and my carry-on—which is normally something you only do before taking a flight, not after you’ve just disembarked from one. (Although I’d left my laptop behind in Beijing, I’d brought my Kindle, my DSLR, my point-and-shoot camera, and my smartphone. I took the phone even though I knew it wouldn’t work as a phone in North Korea—at least not without buying an expensive SIM card, which my tour company had advised against. And even with a SIM card, most of my apps would have been useless as there’s no internet in the country. Still, my phone takes excellent photos and videos, and I use it as an alarm clock, so I’d opted to bring it.) My devices were looked at in a very cursory and perfunctory manner; I wasn’t even asked to power any of them on, let alone to permit the examination of any of their contents.

One element of the inspection process that I hadn’t anticipated is that I had to declare all reading materials in my possession. I needed to list them on one of my landing cards, and show them to the customs agents. My tour company had warned me in advance not to attempt to bring into the country any Bibles (which are banned), or any books or magazines containing any writings about North Korea (with the exception of the informational packet that my tour company had given me in Beijing). I didn’t have any dead-tree books, but I was carrying three issues of National Geographic.

An inspector carefully flipped through the pages of my magazines, presumably to confirm that none of them contained articles about North Korea. I was somewhat surprised that in contrast to the zeal with which they riffled through my Nat Geo issues, the inspectors didn’t ask to see the contents of my Kindle. I think the explanation for this is that they’re mainly concerned about visitors bringing forbidden materials and sharing them with locals. (In May 2014, American tourist Jeffrey Fowle was arrested for leaving a Bible behind in a restaurant in the North Korean city of Chongjin.) Books on Kindles don’t implicate that concern because it’s not really possible to share an e-book, particularly in a country where Kindles aren’t sold and there’s no internet.

By the way, I was informed that when my trip came to an end and I returned to Pyongyang’s airport, I would need to show the inspectors all of the reading materials that I had just declared upon entering. Thus I needed to make sure, for example, not to accidentally throw away an issue of National Geographic if I finished reading it.

Is it true that you have to surrender your passport to the government during the time that you’re in North Korea?

Sort of. Once my possessions passed muster with the gatekeepers at the airport, I was handed over to my local tour guides, who were employed by the state. At that time I was asked to give my passport to one of my two guides, who maintained it in her possession for the duration of my stay in her country. Since she was a government employee, I guess you could say that technically, my passport was in the possession of the state while I was in North Korea. (The guide handed my passport backed to me after accompanying me to the airport upon the conclusion of my tour.)

What did you see in North Korea?

In Pyongyang:

I stayed in Pyongyang, where my itinerary included:

- The unwieldily named Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum (VFLWM), a state-of-the-art museum opened in 2013 that tells the story of the Korean War from the side of the North Korean government (and the story told there doesn’t bear much resemblance to actual history).

The USS Pueblo, a US reconnaissance ship captured by North Korea in 1968, on display at the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum

- Various monuments.

- Kim Il-sung Square, a vast plaza that’s similar to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, only smaller. You may have seen photos of vast numbers of soldiers assembled in Kim Il-sung Square. However, the square was virtually empty when I went there.

Kim Il-sung Square

- A tour of the metro system.

- The house in which Kim Il-sung was born.

- A road called New Scientists Street that’s lined with high-rise apartment buildings that look far more stylish than what I expected North Korean housing to look like (see photo). I was told that thousands of scientists and technicians live on that street (including, presumably, those who’ve been working on the country’s recent hydrogen bomb project). Admittedly, I wasn’t shown the interiors of any apartment units.

An apartment building on New Scientists Street

- Drinks at a microbrewery, where I imbibed a beer made partly from rice.

- An amusement park that my tour guides referred to as “Fun Fair,” but which my internet research suggests is officially titled the “Kaeson Youth Amusement Park.” Although there were long queues to get into any of the rides, members of my group were treated as VIPs, and we were instantly taken to the head of the line for any ride that we wished to board.

- A festival held at a local primary school in honor of a holiday called Foundation Day of the Schoolchildren’s Union of the DPRK. To commemorate the occasion, children participated in a variety of athletic events such as relay races. Also part of the occasion were some singing and dancing performances. The children who participated in these festivities ranged from six to 11 years of age. It seemed that every Western tourist who was in Pyongyang on that day was brought to the school that hosted the event, in order to be shown the spectacle of children having a good time, laughing and demonstrating the athletic, singing and dancing skills that they’ve been able to develop (which of course has nothing to do with the human rights conditions that the kids and their parents live under). Rather than try to capture the essence of that celebration through the imperfect medium of words, I’d like to show you a video I made of it:

A day trip to the DMZ and more:

One of the highlights of my tour was an excursion to the DMZ. Some of the buildings in the DMZ straddle the Military Demarcation Line that has formed the border between North Korea and South Korea since the 1953 armistice, so I was able to briefly walk between the two countries (although that’s as far as you can penetrate into South Korea from the DPRK).

On the way back to Pyongyang, we stopped at Kaesŏng (a former imperial capital of Korea in a time long before the Korean peninsula was divided into two different countries), where we visited a museum in which I saw some historical artifacts and learned a little bit about Korea’s past. We then made an additional stop in a city called Sariwon, which I found boring.

What was the food like?

That’s a complicated question to answer. My guides repeatedly took me to restaurants where I was fed sumptuous multi-course meals—but although I can’t prove it, I’m pretty sure that the food I was given was not typical of what most North Korean citizens consume on a regular basis. It was common in the restaurants I dined at to see few if any other customers who weren’t fellow Western tourists.

I was repeatedly told that the meals to which I was treated represented “traditional” Korean victuals. That may be true, although I would guess that meals of the type that I experienced are far more common in South Korea than in North Korea. During all of my meals, certain food items were very common—among them radish kimchi, potatoes, pork, cold noodles, tofu, bean curd, eggs, and of course rice.

My most memorable meals were:

- A lunch in Kaesŏng, which was called pansanggi (meaning “royal table set”) and which featured a variety of comestibles served in 12 small bowls. One of my local guides told me that the number 12 “shows the highest rank.”

- A dinner at a “hot pot” restaurant in Pyongyang, where various meat, fish and vegetable items were cooked in hot water at the table—similar to fondue.

- A “barbecue duck” meal that served as my farewell dinner, also in Pyongyang.

The 2014 comedy film The Interview, in which Seth Rogen and James Franco portray Americans enlisted by the US’s Central Intelligence Agency to assassinate North Korean despot Kim Jong-un, depicted a building purporting to be a supermarket that was actually a façade—a wall with painted representations of food, designed to fool tourists into thinking that North Koreans can shop at grocery stores with abundant selections of food. I don’t know whether any such “fake supermarkets” actually exist in Pyongyang or elsewhere in North Korea, as none were shown to me. I also don’t know what type of grocery stores can be found in the country; I was afraid to ask to see any.

Along similar lines, I didn’t see any overweight people in North Korea. That observation doesn’t suggest a populace with access to a generous food supply (although Kim Jong-un himself reportedly weighs close to 300 pounds).

When discussing poverty and starvation in North Korea, there’s an important qualification that I should note. After returning home to New York City, I read a book called “North Korea Confidential.” That book draws upon highly reliable sources such as former North Korean citizens who have defected to other countries. Perhaps the most significant insight I gained from it is that, ever since the famines of the 1990s stopped the government from being able to adequately provide for the people, there has been an increasing amount of private enterprise, even though privately run businesses are officially illegal in North Korea. A substantial portion of this economic activity consists of individually run market stalls that are tacitly permitted via bribes to public officials. There is also international trade that is perhaps more accurately characterized as smuggling (again, officially forbidden but de facto tolerated). As a result of the robust underground economy, North Korea boasts a growing middle class that most Westerners never hear about.

In fact, a small number of entrepreneurs have become quite prosperous; not all of the Mercedes-Benzes, Lexuses and BMWs that are imported into the DPRK are driven by officials of the Workers’ Party that controls the country. (I personally spotted a few Mercedes-Benzes in Pyongyang.) In Pyongyang, some of the most successful businesspeople live in a high-end district that locals informally call “Pyonghattan.” Needless to say, my local tour guides in North Korea told me nothing about all of the under-the-table economic activity. Anyway, though many citizens have been able to eke out a comfortable (and in some cases luxurious) existence, the fact remains that numerous North Koreans still live in poverty. The rise of a class of wealthy private citizens has led to vast income inequality. “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need” is a distant memory.

(I was also intrigued to learn from “North Korea Confidential” that the regime’s firewall against outside information has become quite porous; a large percentage of the people have regularly watched South Korean TV broadcasts after illegally modifying their TVs, and increasing numbers of citizens are illegally purchasing foreign films on USB drives (often at the above-mentioned marketplaces).

How were your accommodations?

If Air Koryo is a one-star airline, the Yanggakdo International Hotel may fairly be described as a one-star hotel. Situated on an island, it rises 43 stories. My 40th-floor guestroom had a pretty spectacular view across the Taedong River. The room itself was Spartan in its furnishings and decor. The mattresses on the twin beds were rock-hard; lying down on either of the beds felt like trying to go to sleep on concrete. Although the room was equipped with a flat-screen TV, the TV didn’t work. Similarly, an old-timey-looking console radio built into the nightstand did nothing when I attempted to turn it on.

The food at the Yanggakdo was also undistinguished. When I told you about the delectable eats that I enjoyed in North Korea, I wasn’t referring to any of the meals at my hotel.

There were a few nice amenities in the Yanggakdo; the vast and sprawling basement contains a karaoke bar and a bowling alley. Naturally, given the primacy of my World Karaoke Tour in my travels, I did some singing in the karaoke bar. Also in the basement is a casino, which sadly was closed for renovation during my stay. If it had been open, I totally would have played some blackjack.

Additionally, the Yanggakdo is topped by a revolving rooftop restaurant. I didn’t make it up to that restaurant, though.

Is it true that the Pyongyang metro is fake?

I can confirm that this oft-heard rumor is false. The metro system in Pyongyang is quite real. I know because I rode on some of its trains and walked through three of its stations. I also saw numerous residents of its city riding on those trains and entering and exiting those stations. The stations, by the way, are quite beautiful, reminiscent of the famous metro stations in Moscow that date back to the Soviet era. I think it’s characteristic of totalitarian regimes to spend liberally on public works projects, to project an aura of prosperity even while the citizens are starving.

While a metro does exist in Pyongyang, it’s not very extensive, consisting of a mere 16 stations to serve a city of some 2.6 million people. In comparison, the subway system in my home city of New York counts 469 stations. Still, many Pyongyangites do rely on their metro to get around. It’s one of four forms of mass transit in the city, along with trams, buses and trolley buses.

One form of transportation that you don’t see much of in Pyongyang is automobiles. The broad boulevards of the capital are eerily empty of vehicular traffic. Admittedly, some of the businessmen mentioned above earn sufficient incomes to purchase automobiles, and in some cases, luxury cars. But overall, cars are few and far between even in North Korea’s largest city.

What were your overall impressions of North Korea?

The adjectives “creepy” and “eerie” come to mind. This is a country that not only enforces obedience to current dictator Kim Jong-un, but also mandates reverence of its deceased former despots, Kim Il-sung (Kim Jong-un’s grandfather) and Kim Jong-il (Kim Jong-un’s father). Everywhere you look there are murals of the two dead Kims—even on apartment buildings. Almost all the adults I saw wore pins (which the locals call badges) bearing likenesses of the dead Kims. Bizarrely, I wasn’t permitted to buy one of those badges as a souvenir. My tour guides told me that foreigners are only permitted to purchase such badges if they can prove that they have “love in their heart” for Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. Shockingly, I was unable to satisfy that criterion.

It also felt surreal to be in a country where the government exercises total control over its citizens’ lives and even freely rewrites history. We’re talking about a country that mythologizes Kim Jong-il as having been born on the sacred mountain Paektu (the highest peak in North Korea) even when official records from the former Soviet Union show that he was actually born in what’s now Russia. And with impressive production values, the galleries of the VFLWM (the war museum) tell a story that’s basically an alternate history, in which the “imperialist” US started the Korean war to appease Wall Street “plutocrats”—and in which the brave fighters of the DPRK won the war (even though the war actually ended in a stalemate, with North Korea basically in the same position it was in at the start of the war). North Korea does propaganda really well.

Touring North Korea is a really weird dance; you’re fed a steady stream of lies, but you pretend to believe them, and the government has to know that you know that it’s lying through its teeth.

I lived in South Korea for 4 years and always toyed with the idea of my wife and I going to the North. Not sure if it would’ve been easy or cheap but I always thought about it. I’d like to know more about his visit to the North DMZ because I visited the DMZ from the South and the atmosphere depended on which spot one visited. I remember the organized tour part around Panmunjeom etc to be stiff and serious while it was a bit more chaotic and typical of a Korean shopping center in Goseong. Would be interesting to know more from the author if possible. Anyway, really insightful read and appreciate more info about the north coming out. Thanks for sharing.

@Duke: Although I’ve also been to the South Korean side of the DMZ I’m not familiar with the Goseong portion (I only went to the “main” part where you can go in the North Korean tunnels, etc.). Thus, I don’t have a complete frame of reference for answering the question; for example, I don’t know what is chaotic about the Goseong location.

Initially, I would point you to a Facebook post of mine that contains some additional photos and information about what I saw in the DPRK side of the DMZ and the JSA:

https://www.facebook.com/hbomb1947/posts/10153768760697198

I would say the atmosphere in North Korea’s DMZ was fairly relaxed (except for the part about the soldier riding along in my van as I was driven from one site to another). There was a little bit of a bottleneck when we got there; groups of tourists had to wait for a while in a souvenir shop until the officials were ready to shepherd us along. And when we would get to any particular building we sometimes had to wait until the people already inside had emptied out.

The soldiers, including the ride-along guy, were good-humored and readily posed for photos. We were also allowed to even take candid shots of them as much as we wanted to — an exception to the rule I was told at the start of my visit to North Korea that I was forbidden from taking any pictures of military officials.

I’m not sure if any of this is helpful in answering your question, but if you have any follow-up queries I’ll do my best to address them.

Thank you, Mr. Silikovitz and Johnny Jet for this fascinating first-hand account of visiting the ‘Hermit Kingdom.’ I am planning a visit myself in 2017 via Koryo Tours, and your account is helpful. And reassuring, as you’ve flown Air Koryo and lived to tell!

@Hillari: I’m glad you enjoyed this post and that you found it of value. You will find your own visit to NK in 2017 to be a unique and memorable experience.

Well written,with a whisper of sarcasm.

My sentiments bounced from 1 side of the scales to the other.

While very interesting, I learned very little, as he could not verify

many Western, common perceptions.

I remain in my feelings, that anyone who enters there is not worth a

rescue effort if captured. Their curiousity, is not worth risking anothers’s life to rescue.

Pretty inspiring Johnny! I’m hoping one day the borders are open for everyone to visit (and leave).