I wanted to interview my dad, John Curtin about his 16,000 mile sailing excursion in 2002-2003 because even though it is almost ten years later, he still talks about this adventure as one of the best experiences of his life. There were still so many questions I wondered about, even after talking with him about the journey. After my dad retired from the financial sector in Connecticut after 35 years, he pursued one of his major dreams – circumnavigating South America on a sailboat.

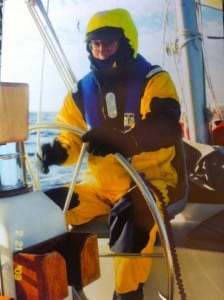

I will never forget getting the call from my dad from the Falkland Islands to tell me that he made it, that he was alive! What he doesn’t share here in this interview is what did happen when their 46 foot sailboat rounded Cape Horn, the most treacherous seas in the world at the tip of South America, known as the sailors’ graveyard. Anyone who reads about sailing Cape Horn will learn rogue waves, which can be as high as a 100 feet, and strong uninterrupted winds make the task literally man versus nature.

“We were surfing,” Curtin said. “We were exceeding hull speed of maybe 9 knots. We were doing 15 to 17. I was just levitating. It was an enormous high. I was thinking, `This is the ultimate.'”

Curtin was attached, but beneath the surface. Forty-four-degree water poured into his boots and chest garments. The wave was so strong that the boat rolled at a 90-degree angle, the mast dipping below the waves. But when it rebounded to an upright position, Curtin used the motion to heave himself back aboard. He was in the water for about 10 seconds.

“You didn’t have time to be scared,” Curtin said. (Chicago Tribune June 1, 2003)

Why did you want to sail around South America?

Because since humanity first set out to circumnavigate the world, Cape Horn has stood as the ultimate rite of passage for every seaman who has dared to venture beyond sight of land. It is not Cape Horn itself, however, that sinks sailboats with attendant loss of life: it’s the waves and gale force and storm force winds that take their toll. Just within 100 miles of the Horn’s southern point, more than 600 sailing vessels and 4000 men lie buried. In essence, rounding the Horn is the ultimate sailing experience that very,very few contemporary sailors are willing to challenge because of the high risk, hostile waters that are unequaled anywhere else on this planet.

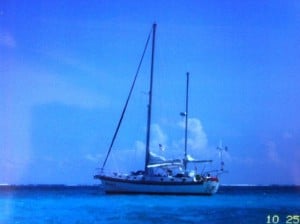

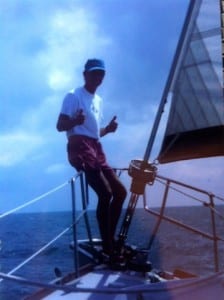

Thus, when I read an ad in the May 2002 issue of Cruising World magazine soliciting crew for this seven-month voyage aboard a 46’ ketch I was filled with excitement and a renewed sense of true adventure. The voyage included 5-7 day layovers in Belize, passage through the Panama Canal, Galapagos Islands, Easter Island, Chile, Falkland Islands, Argentina, Brazil, Barbados and Key West. Having recently retired, I viewed this voyage as an incredible opportunity. It would fulfill a life-long dream to engage in extended off-shore blue water ocean sailing. In my productive working years my sailing experiences had been limited, because of 2-3 week vacations, to Long Island Sound, Block Island Sound and Vineyard Sound, as well as the Caribbean from St. Thomas south to Dominica.

I concluded the time was right for me. My decision? Go for it. I had the time, the skills, and the health, and above all the right attitude. Having graduated from the elite U.S. Army Airborne, Ranger and Jungle Warfare schools combined with my experiences in Vietnam I was reasonably confident that I could prevail under the most demanding of circumstances that this voyage might present.

How long have you been sailing?

I have sailed for over 40 years. I learned by teaching myself how to sail, the same way I

taught myself most things, by reading and doing. My first experience was sailing a rented Sunfish with your mother on Cape Cod Bay. Thereafter, I read voraciously every authoritative book on proper sail handling techniques in different wind and weather conditions, navigation, safety afloat, piloting, anchoring, and radio communications. I also read numerous books written by esteemed sailors to learn how they had prepared their vessels and successfully transited major oceans of the world. I have owned two sailboats, 21’ and 26’ respectively. Both boats were sailed aggressively nearly every weekend during summer months, to include vacations, for many, many years.

What was the hardest part about your circumnavigation around South America?

Maintaining a positive, constructive attitude and relationship with the Captain and crew. There evolved during this voyage a very divisive posture between the Captain and first mate, which spread to certain crew members, that worked to the detriment of all. Keep in mind that we were all strangers before meeting in Mobile Bay, Alabama, the starting point of the voyage. When you confine six sailors to 46’ feet of boat with a beam of just 13’5” (its widest point) I suppose it’s not too surprising that a clash of personalities might occur. They labeled me the ‘diplomat’ because I refused to become involved, having learned the importance of respecting the Captain’s decisions despite my misgivings at times.

The Captain, the first mate and four crew members, including me. Three were from Illinois, one from Florida and one from Martha’s Vineyard.

What was the most shocking/surprising events that happened to your crew?

Chronic seasickness of the crew, particularly the Captain, with the consequent weight loss of over 20 pounds for some, excepting me and one other crew member; the volatile and unpredictable personality and demeanor of the Captain; absence of any sailboats during any passage between ports of call until near the completion of our circumnavigation when I spotted a catamaran sailing toward us just north of Cuba, in the Bahamian channel, this after sailing nearly 16,000 miles. It confirmed my understanding that 99.9% of sailors avoid reaching down to the most feared and most hostile waters of all capes on this planet, the infamous Cape Horn.

What was the most memorable experience on your journey?

Not having the slightest idea of what was going on in the world. The realization that many of

the things we can’t live without are truly unimportant. Doing something REAL – i.e. when you’ve got nothing but your bare life and you’re up against destiny or death; when you’re up against your fortune, whether it goes for or against you. Knowing true adventure is only when the possibility of death exists.

Other memories:

The moonlight dancing and glittering on dark ocean waters forming pathways to unknown destinations.

Our water world with its uncluttered horizons, magnificent seabirds, vivid rainbows, extraordinary sunrises and sunsets and deep blue water.

The moonless, black night-time skies full, from horizon to horizon, with very clear and bright twinkling stars – a time to seek out and discover Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Orion and the Southern n Cross.

A sometimes hostile setting with vicious winds, confused and angry seas, towering thunderhead clouds, hive shaped water spouts and dry and wet lightning scissoring across the sky.

A place of enormous tranquility devoid of the din and pace of modern society. An environment that excludes all our familiar surroundings – trees, buildings, highways, bright city lights and busy people moving about helter-skelter.

The mighty albatross, a very majestic and magnificent long-winged, web footed seabird with its distinctive black eyes and curved tipped orange beak dominating the Southern Ocean; its superlative and incomparable gliding skills and which became my wonderful and unforgettable friend as it welcomed us to its foreboding ocean waters.

Dolphins pursuing and frolicking in our bow waves, in particular the spinner dolphins leaping vertically like ballerinas performing pirouettes. What extraordinary entertainers! Sometimes we would clap and applaud.

Feeling an enormous oneness with nature. Feeling ALIVE, FULL, GRATEFUL, COMPLETE CONTENTMENT – FREE!!!!!!!!!

What were the top three destination you explored?

The exotic Galapagos Islands, Easter Island and Falklands.

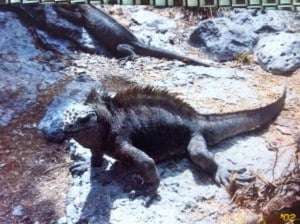

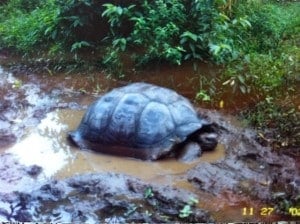

The Galapagos is an archipelago of 19 very unique islands with a habitat unlike no other in

the world. They were discovered in 1535 and stretch over 174 miles from east to west straddling the equator, located 650 miles west of Ecuador, its mother country. The islands are home to numerous native or endemic species, some of which are limited to only one island. The word ‘Galapagos’ is Spanish which means saddle, after the giant land tortoises that populate several of the islands. Interestingly, the earliest Spanish explorers named the archipelago ‘Enchanted Islands’ because of their isolation, desolation and one of the few places on earth where aboriginal man never existed.

All of the islands are of volcanic origin estimated to be one to five million years old. Several islands are covered with lava ripples and cinder cones, the remains of active eruptions. There are also lava tubes or tunnels, some 15 to 20 feet wide and up to 30 feet high. Isabela, the largest island, is composed of six volcanoes side by side, several of which are still active. Giant opuntia cactus grow on the islands and are a source of food for land iguanas. Because the islands are young, in terms of geological time, most of the vegetation consists of cacti and shrubs with flower heads and trees on selected islands.

Of note, the islands are home to:

- The only marine iguanas in the world.

- Unique endemic species, such as the Gapalagos penguin, Galapagos dove, Galapagos hawk, lava gull, flightless cormorant, sea lion, fur seal, red-billed tropic bird AND the blue-footed, masked (white), and blue-footed boobies named for their very clownish mating rituals.

- The swallow-tailed gull, the only night feeding marine bird in the world, nests on only one island.

- Hood Island,aka Isla Espanola, is the only nesting site in the world of the waved albatross.

Memorable moments:

Riding horseback on Santa Cruz Island up into the cloud forest to see the giant land tortoises, lava tubes and vermillion flycatcher.

Snorkeling and swimming among the sea lions and pups on South Plaza Island.

Spotting a red-footed booby resting on our bow pulpit one evening, while on watch, during our passage from Panama to the Galapagos, with still 300 miles to go. It remained there until the next morning.

Wakening one morning while at anchor in Puerto Ayora bay and discovering a seal in our dinghy and me diving repeatedly off our stern pulpit while the crew was ashore.

What place or country was your favorite? What destination wasn’t what you expected?

Keep in mind I had prior to this voyage been to Panama, the Galapagos, had read several books about Easter Island and had travelled extensively throughout Brazil including the Amazon. Thus, these locations and others we visited did not surprise me, though I did enjoy and appreciate the life experiences.

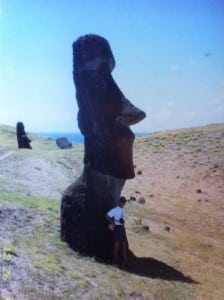

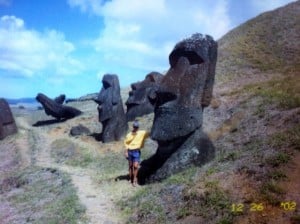

Easter Island is aptly named the ‘navel of the world’ because it is the most remote

inhabited island on our planet. It is located in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean, about 2300 miles off the coast of Chile. The Polynesian name is Rapa Nui, which means ‘our most distant land’. The island forms the eastern most part of the Polynesian triangle, with Hawaii in the north and New Zealand in the south. It is the only Polynesian island where both the native language and Spanish is spoken. The entire island was declared a World Heritage Site in 1995.

The island formed between 3 and 4 million years ago from three primary volcanoes, and there are 104 secondary volcanoes, all currently inactive. The first wave of settlers appeared about 1200 A.D. In 1720, the island was discovered by Europeans on Easter Sunday, thus its contemporary name. It encompasses 64 square miles and is shaped like an equilateral triangle.

The most outstanding features of the Rapa Nui culture are the some 300 hand-carved stone statutes, called Moai, which surround the island all facing inland except seven, aligned side by side, at Aku Akiri, which face west toward Polynesia. According to tradition, they represent the first seven explorers that reached the island sent by King Hotu Matua. The statues represent a most impressive site when approaching by sea. They weigh up to 50 tons each and are upwards of 40 feet tall, carved from volcanic rock. The statues typically rest on large volcanic stone altars, known as aku, presumably dedicated to the memory of the most important ancestors. The biggest question that remains unanswered is how were the natives able to move the statues from their inland construction site over 20 miles, more or less, to the various locations on the perimeter of the island. Further, there are still some 400 statutes in different stages of construction and transport located at Rano Raraku, the principal site of the Moai factory.

There are no rivers, streams or fresh water ponds. Water is extracted from volcanic caverns and craters. Petroglyphs can be found in selected regions. Most of the terrain is covered with very pleasing to the eye green textured short grass, small stands of evergreen trees and numerous high mounds representing extinct volcanoes. There are several beautiful coral sandy beaches and a large number of subterranean galleries and caves that offer unique views of the sea. Hanga Roa, the only town, has a population of about 2,000, 70% of whom speak Polynesian. The horse is the most popular mode of transportation with some wild roaming herds observed. There are some small cattle raising and dairy herds.

Finally, unbeknownst to most, there is an emergency landing strip designed to accommodate the space shuttle.

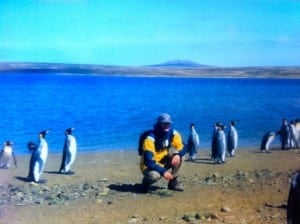

The Falkland Islands were not settled until 1690. They number about 700 islets, with

population of about 2,000 natives and Brits, and are located about 300 miles southeast of Argentina, but are a possession of the U.K. Regretfully, about 30% of the islands are off limits, including beaches, because 20-25,000 plastic mines were buried by the Argentines during the 1982 74 day war between Argentina and the Brits. Only metallic mines can be detected.

Peat soil and white grass dominate the open and unspoiled landscape used primarily for sheep farming. Its Poulton sheep produces the softest wool in the world. Interestingly, the islanders are not fond of fish. Rather, they enjoy eating mutton, lamb, beef, upland geese, cake and biscuits.

The islands are the primary nesting site for the black browed albatross and gray headed albatross, as well home to the leopard seal and several species of penguins, namely the King Penguin, Gentoo Penguin, Magellanic Penguin, Rockhopper Penguin and Jackass Penguin. I travelled overland with a couple of crew in a Land Rover across several adjoining gated farms, known as camps, to a remote seashore location to see firsthand large colonies of King Penguins, Gentoo Penguins and Magellanic Penguins. It was a very impressive and moving experience. We observed that the King Penguin incubates its egg while standing, the Gentoo Penguin while sitting and the Magellanic Penguin in burrows. Their only local predators are the sea lion and sea leopard. However, killer whales have been known to attack the penguins offshore.

In Stanley harbor, the capital, where our boat was secured at the main dock, there were large fishing vessels, known as squid riggers, from So. Korea. We learned that a license is required to fish for the squid in the surrounding waters, accomplished primarily at night, with large arms extending along both sides of the factory ship lit with lamps that light up the surface of the ocean and attract squid to the surface. The annual fees collected approximate $25 million, a primary source of income in addition to that collected from cruise ships that dock enroute to Antarctica.

Cottage style homes dot the Stanley Harbor landscape with their brightly colored red and blue rooftops. On the town pier is a very bright red U.K. telephone booth reminding one of the islanders’ U.K. connection. Not surprising, most islanders work for the government. Hospital/medical care is free, yet their taxes are extreme.

What did you do at sea? Were there ever times when there was no land in sight?

Each day two alternating crew members stood separate 4 hour watches. For example, 8am to noon and again at 8pm to midnight. With six crew, the next two would cover noon to 4pm, then midnight to 4am, and the final two 4am to 8am; in total a 24 hour period. When on-watch you were responsible for navigation, proper sail selection and trim, being vigilant for any hazards or ships on the horizon and at night using radar to detect any vessels in your path and weather fronts which might mean reducing sail. After each watch you completed a log confirming your location – latitude and longitude, compass bearing, distance travelled, wind direction, wind speed, and any pertinent comments. Also we had to check the engine room for any evidence of water in the bilge (the lowest point in the boat).

During off-watch hours you would sleep, fish, read, exercise, sunbathe, and when there was no wind jump overboard for a swim with the boat ladder hung. Because there was crew always sleeping we rarely played any pre-recorded music. We were well beyond the range of any radio station and seldom knew what was going on in the world about us.

Did you celebrate when your boat made it and rounded the Horn?

Did you celebrate when your boat made it and rounded the Horn?

We did! It was 1:30am on Feb. 9, 2003 in gale and storm force winds with steep breaking seas. We detected the Horn 11 miles north of our position on the radar screen. It was a euphoric occasion. My eyes were moist, but we knew we still had to keep our ship safe to complete rounding the Horn. As you know, we almost lost Queequeg shortly thereafter when the boat and this sailor, while on watch, were slammed by an enormous rouge wave which dumped me into the very cold and unforgiving Southern Ocean and buried our vessel under water.

We also celebrated crossing the equator in the South Pacific and South Atlantic Oceans under fair skies and warm temps.

Who cooked while on board? What did you eat?

Each crew member cooked at some time. Some crew, such as the 1st mate, enjoyed cooking more than others. The crew thought I was particularly proficient at the gimbaled stove during rough sea conditions because you had to maintain your balance as the boat was heeling and rolling back and forth in some serious ocean waves. On more than one occasion the 1st mate was tossed on his backside (his ass) as the boat rolled violently in rough seas.

For breakfast: pancakes with syrup and often with peaches, eggs and home fries, oatmeal, cheerios, 100% whole wheat cereal.

For lunch: canned tuna, canned chicken breast, canned meats, and canned fruit.

For dinner: pasta, chicken, steak on rare occasions, fresh fish when caught, oven baked bread, canned veggies, oven baked pizza and chili (yuck!).

Snacks: chips, oatmeal and chocolate chip cookies, fig bars, fresh fruit and canned fruits.

Where are you off to next? Will you be sailing again ? What is your next adventure?

My mind is always open to another unique sailing opportunity. I have now sailed from as far north as Cape Breton Island, north of Nova Scotia to the hostile waters of the Southern Ocean at Cape Horn. I have sailed across Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, up the St. Lawrence Seaway, around the Gaspe Peninsula and in the Bras dor Lakes. I have sailed up and down the Intracoastal Waterway from New York to Miami. As the sole crew member, I am particularly proud to have helped a very experienced captain set a new personal 24 hour single day sailing record of 220 miles off Cape Hatteras, on a 54′ ketch, while on an off-shore passage from St. Marten to Portland, Maine. Its been a great run.

However, I know nothing will ever equal this voyage. There are many fewer people who have successfully rounded the Horn in a small sailing vessel than have stood atop Everest. We came very close to losing our boat and I have read of no one who has been tossed overboard in a small boat at the Horn and survived to tell his story. Was I scared? Certainly not. Why? Because I chose to willingly put myself on the edge and bear its consequences. As a result I grew exponentially from within. What more can one ask from a voyage and journey of this magnitude.

What is the most important lesson you learned?

To be adaptable to the most demanding, changing and unpredictable circumstances. Doing so will enable you to prevail successfully under the most arduous conditions imaginable.

What else would you like to share with me?

Queequeq, the name of our 46’ yacht, is named after the south sea islander and harpooner made famous in Herman Melville’s classic novel, Moby Dick.

Our voyage encompassed five of the seven oceans on our planet, not including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean that we traversed; namely the North and South Pacific Oceans, the Southern Ocean and the North and South Atlantic Oceans.

The Horn was named by the Dutch navigators, Schouten and Lemaire, Jan.29, 1616, in honor of their native town, HOORN, located on the Zyder Zee in Holland, the port from which they sailed. They were the first Europeans to sail around the Horn.

Cape Horn is not a cape, but an island. It is a bold rocky headland, rising 1330 feet, located at the very southern tip of South America. It is the final upward burst of the Andes mountain range.

Happy Father’s Day Dad! I am so proud of all of your brave undertakings. You have always been my true role model of passion, courage, love for learning, appreciation for nature, commitment to adventure, reminding me of what is truly important, and seizing LIFE. Sail forth. – Melissa Curtin (June 2012)

“Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.”– Mark Twain

Thanks Charley :)

Excellent interview and account of the voyage. Congratulations John and Melissa.